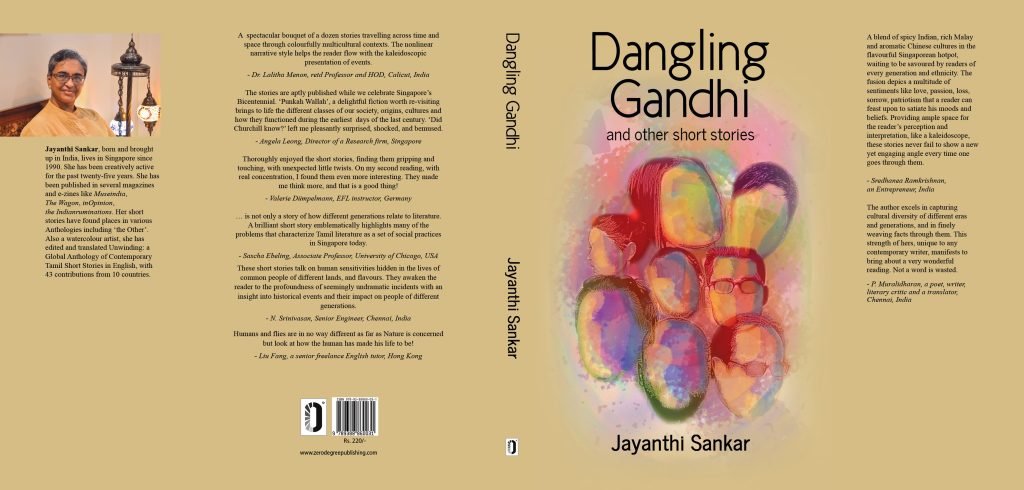

Interview with Jayanthi Sankar, the author of ‘Dangling Gandhi’

Jayanthi Sankar, born and brought up in India, living in Singapore since 1990, has been creatively active from 1995. While she is in the process of writing her first novel, this is her first book of short stories collection – Dangling Gandhi, coincidentally published three days before Gandhiji’s 150th birthday. She has edited and translated the Global Anthology of 43 contemporary Tamil short stories ‘Unwinding’-with contributions from 10 countries has been published in July 2019. She has been published in several magazines and ezines like the indianruminations, museindia, The Wagon, inOpinion. Her short stories have found places in various anthologies including ‘the other’. She has been invited to participate in the panels of literary festivals such as (Asia Pacific Writers & Translators) APWT 2018 at Gold coast, Singapore Writers Festival, Seemanchal International Literary festival, Asean- India Pravasi Bharatiya Divas Writers Festival. Also a watercolour artist, she has been a freelancer for more than a decade and a half, with a three years of experience in journalism. jeyanthisankar28@

R. Sredhanea is a food technologist and psychotherapist with a lifetime goal to establish a non-profit organisation that provides quality nutrition and education for the mentally disabled kids. She is presently the CPO of Neolithic Foods Private Limited, Theni. Her flair for the English language and inspiration from the works of Dan Brown, Jeffrey Archer, and Amish Tripathi nudged her to try her hand in fiction. Her two unpublished novels, “The Chord” and “The ugly duckling” strive to shout out her love for the two worlds- Literature and science. “Mirabhai” a translation of the renowned Tamil author Madhumitha’s work is her debut as a translator. She wishes to publish both her books and widen the horizons of Indian youth beyond Young Adult fiction.

————————————————————————————–

Sredhanea Ramkrishnan in a dialogue with the Author Jayanthi Sankar

July 2019 – via email

(On Dangling Gandhi and other short stories)

Sredhanea Ramkrishnan: Let’s begin with the title, what do you intend to send across to the readers by this title?

Jayanthi Sankar: As you have already read the book, so you would know that in the title story Dangling

Gandhi, is only a subtle metaphor. Although my favourite story of the collection is not this, I decided on this

title for the book as it suits all kinds of uncertainties and doubts of our times, the world over, on Gandhism as

well as the nonviolence he upheld, becoming more and more debatable in this modern world. However, the

story hardly touches on these, interestingly.

Sredhanea Ramkrishnan: In that story, an older adult’s love for his motherland is brought in by a jubilant

flashback. Isn't it strange how attached our human minds are to our land and our past? And all that a soul

needed before its departure was a whiff of reminiscence!?

Jayanthi Sankar: The story did just that – to capture the childhood memories of the departing soul amidst the

interestingly woven present life and the voices of the next two generations. A gentle stroke of the zero brush of

multicultural diversity helped add value to this particular painting of words.

Sredhanea Ramkrishnan: We are all well aware of the dreadful imperialism, but your stories paint a different

shade of post-colonialism that none of us even imagined, don't you think it might offend or shock a patriotic

mind?

Jayanthi Sankar: However dreadful a period may be, it will certainly have other sides to it. At least one angle

other than what has always been projected to the future generations. When you say ‘none of us even imagined’

shows how we are all preconditioned to think other than what has been prescribed to us.

Haven’t we seen Schindler in the famous movie? Are we going to argue that that character is going to offend

the Jews? Such a character or depiction creates debates, and that’s the sole purpose.

In the same way, my stories are not meant to offend anyone or deliberately crafted to paint a different shade but

only to raise questions and to provide ample space for debates. They are, but many flashes and images of real-

life gathered in my memory over decades since my childhood, from what I heard from seniors in the family,

relatives, extended families, and friends. Readers are sure to feel my neutral tone as they are not biased in any

way.

Sredhanea Ramkrishnan: As we all are slowly moving towards being global citizens, is patriotism even relevant

anymore?

Jayanthi Sankar: Yes, patriotism is slowly losing its meaning in the modern world but, knowing the past and

the period when patriotism in its truest sense existed and had its relevance becomes important to confront our

modern day challenges. They may be of border issues, immigration, and terrorism of any kind. Values and

issues do vary, but there is always a string of continuity.

Sredhanea Ramkrishnan: When we see the twelve short stories, the sequence seems to be chronological, almost

from the 1850s till present date, but with a higher leaning towards the period of Independence of India. Why

does the part seem to interest you the most?

Jayanthi Sankar: Well, it’s interesting to note that you have read them as one whole unit. I guess my interest in

the Independence of India could have arisen from the life experiences seniors shared along the journey of my

growing up years and the school days’ subject of Indian history. Nothing more than any of us would normally

know.

Sredhanea Ramkrishnan: Tell us a bit about your journey and evolution as an author and a human being.

Jayanthi Sankar: Although I remember growing up as the eldest of the four children in the family, turning a

second mother to the youngest when I was nine a lot of internal debates and thought processes had happened

with less than optimum reading, I’d say. I used to be always quiet and responding more in syllables than words,

everything around me set me to think though I never used to express.

Having grown up in different states in India, naturally, I got exposed to different languages, people, and

cultures. I never knew back then that I would write one day.

Later, when I came to Singapore as a young mother of my elder son, the libraries here fascinated me. My

reading increased unimaginably. I used to read in English and Tamil. I started writing fiction in 1995 in both the

languages and eventually decided to focus on one language at a time. And in the past 4 to 5 years, I have turned

my focus to writing primarily in English.

The voracious reading shaped the human being that I am today with the writer being is only a byproduct.

Reading continues to catalyst the evolution of both in me, also resulting in spiritual progress.

Sredhanea Ramkrishnan: I would like to know how you came up with the idea of making the floods the centric

theme or the connecting factor between two differently timed yet profound sorrows and what effect you expect

on a reader with a fleeting note about Winston Churchill in the story.

Jayanthi Sankar: ‘Did Churchill know?’ was written long before the recent devastating floods of Kerala.

When I witnessed the images of the floods, I was intrigued, especially because I had lived through a similar one

in my fiction during its creation.

This story carries two tiny canvases of the older man and Jack with a very vast and broader canvas of the tea

estates that began during the colonial periods and how the devastating floods destroyed the hilly region.

I’d been to Munnar a few years back for four days on holiday with friends. The hill station with the surrounding

ranges of hills captivated me just as the Winston Churchill bridge/arch did. I felt the arch stood there heavily

carrying the remnants of the past. Ironically, Churchill detested India and Indians, and that makes us, the people

of the later generations raise several questions.

The story comes under parallel storytelling. It was not planned. I discovered that the story fell into that

category, only upon reflecting later on.

Sredhanea Ramkrishnan: Physical disability is often looked upon as a bane; for the first time, your second story

depicts a hearing and speech impaired man as an asset rather than a liability. Did you want to bring out this

point in particular or was it just an unintentional note?

Jayanthi Sankar: It is more complex than that in the story ‘Punkah Wallah.’ For Herman, Mani may be an

asset. But when you read a little deeper, you will also feel that an act that appears to help many a time becomes

the exploitation of the situation.

The protagonist of this short story represents the community of fan men. Colonial English of not only the

subcontinent of India but also of Malaya used these men to do this job of fanning them. Those were the days

before Electricity came widely to the eastern part of the world.

My dad used to have an elderly friend when I was in my mid-teens while we were in Shillong. He was a Sardar

who used to share things about his ancestors, childhood, and partition. He said there were many of his relatives

in the then British Indian army and many worked as fan men and that one such lad was taken away to far away

Malaya. The memories of those interactions surfaced in me to craft this short story, one of my favorites.

Sredhanea Ramkrishnan: Do you mean to say animal-loving and animal eating/ killing pests and insects the

complete contrasts and exclusive of each other?

Jayanthi Sankar: On the contrary, in ‘The peacock feather fan’ I depicted the interdependency of not just

animals, insects and pests but also the humans. There is an inevitable, invisible chain similar to the food chain

also at workplace, the institution of family and marriage and everywhere. And this chain also has prey that turns

a predator or a predator turning to be a prey at some point of time, and that’s what the story intends to bring

about.

Sredhanea Ramkrishnan: Subtle yet profound expression of the pain of betrayal of trust in ‘Mobile Dictionary’

which raises in the reader a question. Which betrayal do you think would have been more hurtful, by the family

member or the dotted upon friend?

Jayanthi Sankar: The betrayal by the friend or mentee of the story in today’s world would not even be a

betrayal at all. In those days, especially in the community that the protagonist belonged to such a betrayal meant

heinous.

There are other nuances in the story like Ramasamy Iyer who could empathise the hunger of his beloved cow,

could not even digest what his 20 years old sister needed and was after.

This story is typically character-driven. The protagonist is based on my paternal grandfather, who founded three

primary and high schools in the Southernmost of the present state of Tamil Nadu, during the colonial period. An

erudite who memorized the dictionary used to be revered by his English friends, I have been told. I have never

met him. He died when my dad was hardly five years old.

Sredhanea Ramkrishnan: In love, life, and separation, the significance of sacrifice has been well talked about

by all, but timing? Isn’t that the most crucial of it all?

Jayanthi Sankar: We continue to learn in this school of life, don’t we? The timely favourable happenings bring

us happiness and joy and a stronger belief in humanity and untimely unfavourable incidents just the opposite.

Ironically, the whole unpredictability of life and the uncertainties make our lives. Those who realize this and

embrace the truth to live with the flow find peace with life. In ‘The Pavilion’ the love and untimely separation

in the past bring into this world the protagonist.

Sredhanea Ramkrishnan: Poverty vs. luxury well explained by a bus ride, a child's kindness and observance

shine through, do you think as we grow into adults we lose sight of humanity or are we too selfish to observe

the need of others?

Jayanthi Sankar: It’s more to do with the conditioning of the mind rather than the adulthood by itself. Those

who grow into adulthood with some awareness that the conditioning is almost inevitable, escape this to some

extent. Even those who are already adults and can unlearn are capable of shedding at least portions of the

conditionings. In these, I believe, lies the selflessness and humanity. Though ‘Beyond Borders’ portrays a

typical bus ride in Singapore, a simple story runs through in which I guess the unconditioned mind of the child

has naturally come out well.

Sredhanea Ramkrishnan: Again, strength and talent despite a physical disability. What inspires you to highlight

the good side of physical challenges?

Jayanthi Sankar: I didn’t think of highlighting the good side of physical challenge. I created the character

Venu in ‘The Pavilion’ who lives his life normally like his peers despite his condition. It’s neither to glorify

physical challenge nor to bring sympathy in the readers but to show perhaps his inner strength, more through

the feel the reader gets rather than through words. And it used to be common those days to come across people

affected by Polio.

Sredhanea Ramkrishnan: Allegory, the most difficult form of literature seems to be your forte. What made you

prefer it over other styles like flash fiction or vignette? Do you think the readers would be able to find the

essence of the story in the same thread as you wish them to?

Jayanthi Sankar: Normally, I play with the theme and characters in my mind before I start crafting. Therefore,

I let the theme and content choose the form. That having said, I love all other forms, and I hope to try my hand

at them as well.

Different readers can read these stories in different depths. Albeit the stories are in a simple language, I won’t

deny that they are layered and require some effort to understand well enough. I’ve been blessed with readers

like you who read in some places beyond my intent and also those who sought my guidance before reading the

second time. There were also a couple of readers who said they were unable to go into them and I could

understand.

Sredhanea Ramkrishnan: Suffering is the ones left behind, not the dead. Aren't we all in a way facing the

consequences of our ancestor's actions? Good or bad?

Jayanthi Sankar: The dead leave behind both good and bad residues for us to endure, I suppose, just the way

we will be when we leave.

‘Mother’ talks about the devastating fury of Earth turning upside down the lives of an entire lineage of an

English family settled in Shillong.

Sredhanea Ramkrishnan: One can write about emotion in detail only if one had experienced it, loss by death or

love and ways of overcoming the loss seem to be better depicted in your stories. Is there a reason behind this?

Jayanthi Sankar: This moment, when I read your question, I am thinking. And except my empathy, I have no

reason that I can think of because, fortunately, loss by death or love and ways of overcoming the loss have not

been my life. Those effective depictions in my stories, for me, reflect my empathy. I tend to live those lives

while conceiving and crafting.

If a writer can write well about death only after he experiences it, is it even possible for us readers to have texts

depicting death?

I believe empathy is capable of creating the emotion in any writer even if she had not experienced that

particular emotion.

Sredhanea Ramkrishnan: As an author, how do you think writing this book helped you?

Jayanthi Sankar: Only ‘Read Singapore’ was written back in 2011. Writing the other 11 of the stories over

four years was so far the best creative phase that I loved and enjoyed.

I am writing a novel in English right now, and Dangling Gandhi has become the creative personal record that I

hope to break. And that generates so much of motivation and drive, although, I have to accept that there are

times when the other end is also felt. These swings by themselves are so interesting to watch as I currently plan

the novel chapters.

Sredhanea Ramkrishnan: Who do you think are your target audience?

Jayanthi Sankar: All readers who enjoy literary fiction, Literary critics, Academics, and the serious readers of

the western world who are eager to know more about literature, culture, lands, and people of the east. I am very

sure the simple language will help the readers enjoy these varied, layered, nonlinear narrations, and assimilate.

Sredhanea Ramkrishnan: Is feminism just supporting equal rights and liberating women, or is it much deeper

than that? Maybe not judging anyone for their actions and respecting their journey?

Jayanthi Sankar: ‘My mother is feminist’ aims to tell that respecting others’ journey is just the basic. It tells us

that a man though a son would still see his mother as a feminist if he searches for reasons to justify his action

that he has mixed feelings about – undergoes an unexpected after-effect.

To me, feminism with all its various shades is deeper than those two. Constantly evolving as we human evolve,

feminism too undergoes constant changes.

This story was included in the Anthology, ‘the Other’.

Sredhanea Ramkrishnan: Are love and pain co-dependant? What's your take on unrequited love? Do we hate the object of our love that left us or ourselves for having fallen for the wrong person?

Jayanthi Sankar: I think it’s both – the love turning into hatred for the one who left and also upon self for

having fallen for the wrong person. Natasha in ‘Am I a jar?’ is hurt and confused for the same reasons. As far as my knowledge goes, Love mostly comes along with heartaches and naturally unrequited love would mean

naturally tremendous pain.

Sredhanea Ramkrishnan: Life, love, loss, you've covered them all, is satire too latent in your words?

Jayanthi Sankar: I hope to search to discover, which I’ve already started.

Sredhanea Ramkrishnan: It's good to know where we come from and respect our culture but do you think we

should branch out and flourish or still be grounded and attached to our roots

Jayanthi Sankar: Knowing the roots can give the feeling of a groundedness wherever you may go. With the

globe shrinking, it’s only natural that one branches out to explore and flourish as he takes his roots within him.

Some are unable to part with their roots and land and therefore end up returning sooner. Momo in ‘The peasant

girl’ is one such girl.

Sredhanea Ramkrishnan: Indian, Malay, and Chinese cultures beautifully intersperse in your words. Being an

Indian descent settled in Singapore, tell us what impact the history of Indian, Chinese and Malay, and

mythology and politics have on your writings.

Jayanthi Sankar: Comprising not just the local ethnic groups but also of the immigrants and the floating tourist

population, Singapore is almost as diverse as London. Two hundred years old modern Singapore is

comparatively young, though. Due to her geographical location, one of the earliest ports in the Asia Pacific,

diversity has always been her specialty.

When one lives here for nearly three decades, it’s very natural that she gets exposed to diversity. It is not too

unique when she happens to evolve as a writer, and she depicts that.

In my formative years, I was fortunate to have been exposed to a multicultural environment as my dad being a

central government engineer used to be transferred all over the subcontinent. So I grew up in many states.

Shillong was one such beautifully diverse place.

Sredhanea Ramkrishnan: Having read about, heard, and even being an immigrant, what do you think is the

biggest shock an immigrant faces? Cultural, social, economic, or educational?

Jayanthi Sankar: I think it depends much on the immigrant’s exposure, childhood, upbringing, and other

backgrounds. For instance, 30 years back when I migrated to Singapore, because of my exposure I could see the

city as naturally diverse whereas many ladies came directly from their home town could not take the culture

shock. They had lived all their lives in their village, or town, or city, or state.

Here, I am reminded of a friend’s friend, a guy from IIT Chennai, graduated, and had gone to the US. Decades

back, not exposed to other cultures when the Information technology was not as advanced as it is now, he had a

culture shock of seeing the cleavages of the American women and returned within months to his native place.

Sredhanea Ramkrishnan: If you'd written these stories maybe a few years ago, do you think they'd have shaped up the same way?

Jayanthi Sankar: My creative journey started in my late twenties, and so now, in my mid-fifties, my

storytelling has evolved. I’m better exposed and experienced in forms and techniques, and therefore, I think

these stories have come out at the right time for these themes that stayed in me for decades would not have

shaped this well, if years ago.

Sredhanea Ramkrishnan: What recent/ past life experience of yours readied you to pen down these stories?

Jayanthi Sankar: Like I said earlier, my experience from enriched explorations in both reading and writing has

brought me to this phase, and naturally. Most of these stories have always been churning deep in me all the

time, only waiting to be created, I suppose. When the stories surfaced I could give them the needed shapes.

Title: Dangling Gandhi

Author: Jayanthi Sankar

Genre: (Literary) fiction/short stories

Published by: Zero Degree publishing

Year: 2019 / ISBN: 978-93-88860-03-12

Pages: 154

Price: Rs.220

Credit: ScarletleafReview, CANADA